The Molecular Fingerprint: An Introduction to Raman Spectroscopy

Imagine if you could shine a laser pointer at an unknown substance—a diamond, a pill, or a speck of paint on an ancient canvas—and instantly know its exact chemical composition and molecular structure.

That isn't science fiction; it is the reality of Raman Spectroscopy.

Named after the Indian physicist C.V. Raman (who won the Nobel Prize for its discovery in 1930), this technique has become a cornerstone of modern material science, chemistry, and even forensics. But how does it actually work?

1. The Basic Concept: It’s All About Scattering

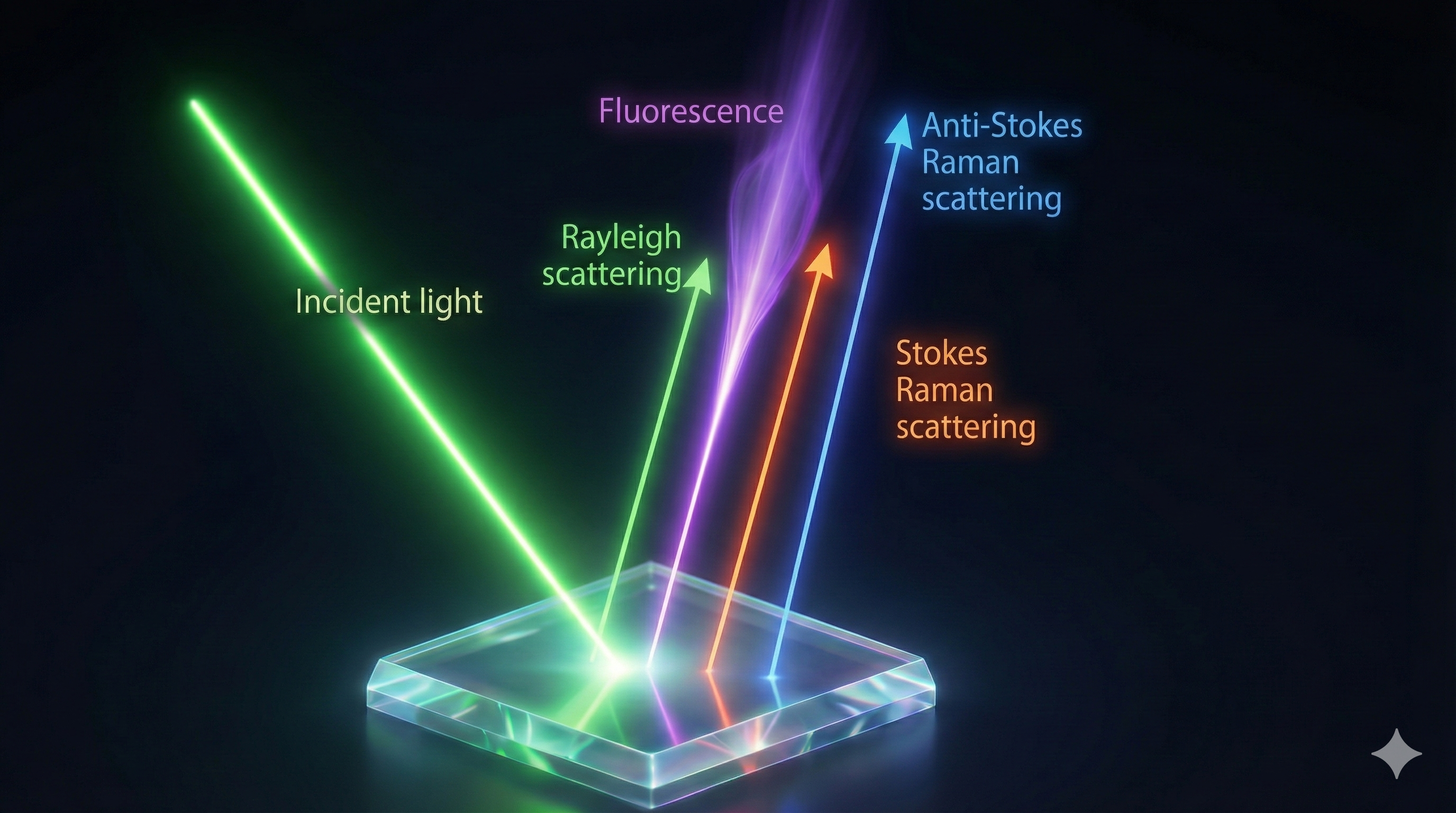

To understand Raman, you first have to understand what happens when light hits matter. When photons (light particles) interact with molecules, they can scatter in two ways:

Rayleigh Scattering (Elastic)

This is the most common type of scattering. Imagine throwing a tennis ball against a brick wall. The ball bounces back with roughly the same speed (energy) it had when you threw it. * In Physics terms: The scattered photon has the same wavelength as the incident laser source. * Result: No new information about the material's energy levels is gained.

Raman Scattering (Inelastic)

This is the rare, interesting phenomenon (occurring in only about 1 in 10 million photons). Imagine throwing that same tennis ball at a moving truck. * Stokes Shift: If the truck is moving away, the ball bounces back slower (less energy). The molecule "stole" some energy to vibrate. * Anti-Stokes Shift: If the truck is moving toward you, the ball bounces back faster (more energy). The molecule gave energy to the photon.

In Raman spectroscopy, we measure this change in energy. Since every molecule vibrates at specific frequencies depending on its bonds (like a unique musical chord), the energy change tells us exactly what bonds are present.

Key Takeaway: Raman spectroscopy measures the shift in light energy caused by molecular vibrations.

2. How the Instrument Works

A typical Raman setup is surprisingly elegant. It consists of three main parts:

- Excitation Source: A high-intensity laser (usually green, red, or blue).

- Sampling System: A microscope to focus the laser onto a tiny spot on the sample.

- Detector (Spectrometer): This filters out the intense Rayleigh scattering (the "noise") and detects the weak Raman scattered light (the "signal").

3. Reading the "Fingerprint"

The output of a Raman experiment is a graph called a spectrum. * X-Axis (Raman Shift): Measured in wavenumbers ($cm^{-1}$). This represents the energy difference. * Y-Axis (Intensity): How strong the signal is (how many photons hit the detector).

What do the peaks tell us?

- Peak Position: Tells you the chemical identity. A peak at $1332 \ cm^{-1}$? That's the characteristic vibration of the carbon lattice in Diamond.

- Peak Width: Tells you about crystallinity. Sharp peaks usually mean a high-quality crystal; broad peaks suggest an amorphous or disordered material.

- Peak Shift: Tells you about stress and strain. If a material is being squeezed or pulled, the bond lengths change, shifting the peak frequency slightly.

4. Why Is It So Useful? (Applications)

Raman spectroscopy is non-destructive and requires very little sample prep, making it versatile across industries.

| Field | Application |

|---|---|

| Semiconductors | Measuring strain in silicon chips or characterizing 2D materials like Graphene and MXenes. |

| Pharmaceuticals | Verifying that the active ingredient in a pill is distributed evenly without destroying the pill. |

| Art & Archeology | Identifying pigments on Renaissance paintings to determine authenticity or restoration needs. |

| Security | Detecting explosives or narcotics inside transparent containers (since the laser can pass through glass/plastic). |

5. The Pros and Cons

Advantages

- Non-destructive: You don't have to burn, dissolve, or cut the sample.

- No sample prep: You can often measure samples "as is."

- Works in water: Unlike Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, water doesn't absorb the signal strongly, making it great for biological samples.

Limitations

- Weak Signal: The Raman effect is very weak. It requires sensitive detectors and long exposure times.

- Fluorescence: If a material is fluorescent, it glows brightly when hit by a laser. This glow can easily drown out the faint Raman signal, ruining the data.

- Heat Damage: The intense laser can sometimes burn delicate samples (like dark biological tissues).

Conclusion

Raman spectroscopy provides a window into the molecular world through the simple act of scattering light. Whether you are engineering the next generation of solar cells or checking the purity of a diamond, this technique offers a precise, non-invasive way to "see" chemistry in action.

So, the next time you see a green laser pointer, remember: there is a whole world of molecular vibration dancing in that light, just waiting to be measured.